Sitting in the Folger Library some years ago, I read a typically abrasive letter written by Charles Macklin to his manager at Covent Garden Theatre, George Colman, in 1770. Macklin, never shy about his own sense of self-worth, argued for a higher salary:

for your Books can shew that I brought to your Theatre, in ten Nights acting, between four & five hundred Pounds more than Mr. Powel & Mrs. Yates in the same number of nights that they both acted together and I am confident that I can now bring more money than any of the Performers that now belong to it, exclusive of a new Pantomime or the attraction of a new Piece being added to their Performance. and in that case Experience daily shews that it is not the actor’s Performance that has so much the power of filling the House as the novelty that is added to it.

Charles Macklin to George Colman, 16 [Oct] 1770, Folger Library MS, Y.c.5380 (3)

Macklin’s bold negotiation brought a smile to my face but I then began to think about the account books to which he referred. Was there—or could there be—a way in which one could measure the financial value of an actor to a theatre and how it changed over time? How did the theatre manager determine salaries for his acting company and what other costs did they have to worry about? Could ‘novelty’ be quantified from those costs? Was it possible to extricate the dancer from the dance and determine whether the performance receipts generated were down to the actor, to the play, or to some other factor? How important were pantomimes to the financial stability of a theatre? How did these issues vary, if they did, across both the main winter theatres of Drury Lane and Covent Garden? Several other questions began to bubble in my mind about the research possibilities that could be opened up through the analysis of financial information.

I began to do some reading around. As any theatre historian of the period will know, Judith Milhous and Robert Hume’s work was central to this topic, especially Milhous’s ‘Reading Theatre History from Account Books’ in Players, Playwrights, Playhouses: Investigating Performance, 1660–1800, which laid out many potential benefits of the analysis of theatre finance. Equally, reading David Taylor’s chapter in The Oxford Handbook to the Georgian Theatre, 1737–1843 reminded me that we knew so little about theatre managers despite their remarkable cultural power in the period. The chief enabling factor for the project was the remarkable work done by the London Stage Database project by Mattie Burkert and her team in digitizing the weighty tomes of The London Stage, 1660–1800: A Calendar in an open-source website. Fortunately for me, Leslie Ritchie had also done some wonderful work in transcribing and coding the data from the Cross-Hopkins diaries, also held at the Folger. Having access to this data made the project feasible and, with the help of many people, a grant application to the European Research Council was submitted.

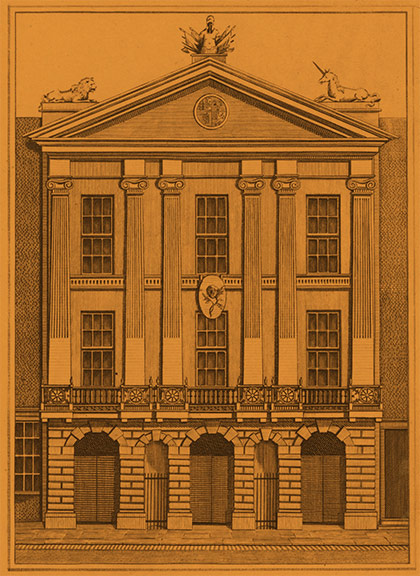

The ambition of the project is to harness the remarkably rich (if patchy and inconsistent) financial archives of Covent Garden and Drury Lane, 1732–1809. By fusing archival research, digital humanities, and econometrics, this interdisciplinary project will construct a foundation on which eighteenth-century theatre studies can build its next generation of scholarship. These archives, largely held at the British Library and the Folger Library, are comprised of a considerable run of account books, journals, and ledgers for the period that give very specific detail on revenues, ticket sales, salary costs, other costs, and audience profiles, details that offer an unprecedented level of granularity to the analysis of Georgian cultural production. We will use them not only to illuminate our understanding of theatre in the period but to showcase how econometric methodologies might be used for humanities research questions more broadly.

Macklin’s letter to Colman in October 1770 was met with indifference and the actor headed to Dublin shortly afterwards. But he was perhaps ahead of his time. In April 2021, Kevin De Bruyne, a football player for Manchester City, negotiated a significant pay rise and contract extension after using a data analytics firm instead of an agent. Although our project is too late to help Macklin, the reported £83m De Bruyne will be paid as a result demonstrates the power of such empirical analysis.

David O’Shaughnessy